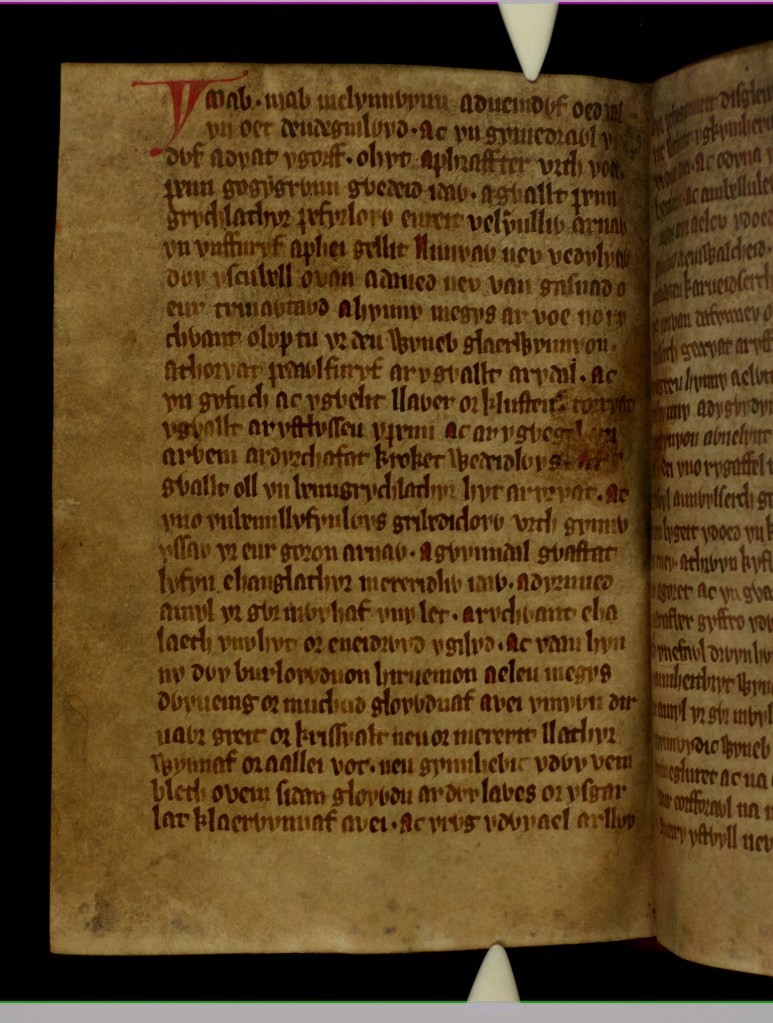

A page from a medieval mss copy of Ymborth yr Enaid

Ymborth yr Enaid (Sustenance of the Soul) is a text written in the 13th century by a member of the Dominican order of friars in Wales. It sets out a guide to mystical experience and suggests a number of practices to enable such experience for members of the order. As such it is comparably rare in the literature of medieval Europe in that the orthodox view of the Church at the time discouraged attempts to experience divinity directly rather than through the established rituals of the Church, and held that such experience, if it did come, should come unbidden and then only to special individuals whose experiences, if recognised by the Church, might well lead either to sainthood, or, particularly in the later Middle Ages, to accusations of heresy for the individuals concerned.

The fact that Ymborth yr Enaid was written in Welsh rather than Latin suggests that it was intended as a guide for ordinary members of the Dominican order rather than as a contribution to theological debate, and also meant that it would have escaped the attention of a wider audience outside Wales. One scholarly monograph on the text* suggests that a context for the production of the work in Wales might be the native tradition of the awenyddion as described by Giraldus Cambrensis in the 12th century. Although this tradition is more likely to have arisen from remnant druidry, and is described in terms of inspired prophetic ability, it is suggested that the existence of such a tradition would have provided the author of Ymborth yr Enaid with a context for a guide to mystical experience, or, as the opening section puts it, to “the ecstasies” and ”visions” whch may come “from the Holy Spirit” and “the nine orders of angels”. The fact that some parts of the work are in verse, and others in what might be termed ‘heightened prose’ indicate that the author was also relating personal inspirations alongside the more mundane passages of discursive argument.

The starting point for those seeking mystical experience is the conventional advice which would be given to all members of medieval monastic orders: avoid sinful thoughts and practise virtuous acts. This would attract the love of God which should be reflected to others around the practitioner. Having achieved this ideal state, the specific practices to achieve mystical experience can then begin. The author’s own experiences, as related here, concern a vision of the young Jesus and advice given by him to the poets that he should be the object of their praise. Clearly, the author was considered to be one of these poets and the instructions for achieving mystical visions follow the advice often given to poets who might compose intially by lying down in a darkened room shaping the verse in their minds. So the seeker of mystical experience is likewise directed to do so at quiet times of day or at night in bed “after midnight until daytime”. The aim here is to induce trance-like states, variously defined as “twofold”, “threefold” and “victorious” trance, each stage taking the practioner further from the physical flesh until a total union with the divine is acheived. Also significant is that the trances are to be experienced by individuals quietly in private spaces rather than as part of community worship or ritual, although part of the preparatory instructions include chanting a Latin hymn which the author has translated into Welsh metrical form. This should be done until “the heart dances and sings with devoted love”. While they are clearly distinct, and operate within different contexts, the similarities between the instructions to poets and to the Dominican friars, and between the trance states of the awenyddion and those which might be achieved by the friars, suggest a persistence within Welsh culture in the early medieval period of the notion of spiritual, poetic and prophetic activity arising from mystical experience, and spilling over from the bardic tradition of the divine origin of the awen to the Christianity which had become the approved mode of spiritual experience .

If the medieval Church, in general, tended to be suspicious of the bards and of poetry as a medium for individual expression, what we find here is a work in which poetry is integrated into both descriptive and imaginative prose detailing practices which may be undertaken by individual members of a religious order which was part of the medieval christian establishment. It is likely, that the anonymous author was also a bard as the verses included in the text display knowledge of techniques that are likely to be the result of bardic training. Analysis of the style also shows it to be comparable to works of imaginative prose tales of the period, even leading to suggestions of possible common authorship.* Be that as it may, the author was certainly gifted with the awen and able to accomodate older ascriptions of its divine origin to contemporary religious orthodoxy. The stories that shape divine inspiration change over time. The mythologies that give it form and make it accessible to expression vary across cultures with different emphases, aspirations and political priorities that may seek to channel it to orthodox interpretations or even suppress it entirely. But whatever the language of religious expression, it seems that divine inspiration is a universal quality which can shape itself to any available medium that doesn’t seek to stifle innovative expression of visionary experience. The question remains, of course, as to whether it comes from a single source which is experienced differently in different cultures, or whether the sources are various but lead to a similar mode of human experience. Suffice to say that the experience itself is definitive for those who have it.

* R. Iestyn Daniel A Medieval Welsh Mystical Treatise, (University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, 1997). The author suggests that the idea of divine poetic inspiration originated in “ a Christianization of a pagan belief that the poet, when inspired, was possessed by an impersonal underworld power”.

A discussion of the manifestation of this idea in the early welsh bards can be found in : Y Chwaer Bosco ‘Awen Y Cynfeirdd a’r Gogynfeirdd’ Beirdd a Thywysogion (Caerdydd, 1996).

R Iestyn Daniel has also edited an edition of the medieval text:Ymborth yr Enaid, (Caerdydd, 1995).

For a discussion of the place of Ymborth yr Enaid in early Welsh religious thought and a partial translation of the text into English see: Oliver Davies Celtic Christianity in Early Medieval Wales (Cardiff, 1996).

One response to “Ymborth yr Enaid”

Thanks for sharing. The title ‘Sustenance for the Soul’ alone is delightful in itself and the notion of chanting until “the heart dances and sings with devoted love” really resonated with me. It does sound like this evidences more ecstatic and visionary practices associated with awenyddion being incorporated into the Christian mystical tradition.