-

Awenau hear me

aid my song

As I write of the one

who is ever young:Maponos, the son

of Matrona – Mabon

Who from Modron was taken

out of the light of the WorldInto the darkness of unWorld

he was Maponos and not-Maponos

When the darkness held him

and he held the darkness about him.Matrona – who is Being – searched

but he was in not-Being;

She was in every place in the World

but he was in not-World,So she went there, and Being

was not, and light faded from World.. .

.Who was it held the key

to release them? Many storiesTell of heroes in the spring of World:

Manawydan breaking the spell

That lies on the land

for Rhiannon and Pryderi to return,Cei and Bedwyr riding the salmon

to find Mabon and bring Arthur

To release him from Caerloyw

out of the darkness into the light..

. .O Awenau, he is the one

who holds the harp, the lute, the lyre,

He is the one who contains your song,

He is the muse of Fire!.

-

The Greek poet Hesiod (c. 8th century b.c.e) prefaced his Theogony (Stories of the Gods) with an appeal to the Muses “Let us begin our singing”, and tells first of them. There were nine born to Memory: “Nine nights Zeus lay with her …. and she bore nine daughters”. They went then to Olympus “glorying in their beautiful voices and singing divinely”. Hesiod then tells how they inspire divine utterance in those they favour: Such is the Muse’s holy gift “and they told me to sing of the blessed ones who are forever, and first and last always to sing of themselves”. So Hesiod begins the work of writing his Theogony. Addresses to the Muse or muses also begin the Homeric Hymns to each of the gods from the same period, and Homer himself begins both his Iliad and his Odyssey with a similar appeal.

For the early Welsh bards the Muse was Ceridwen with her cauldron the source of Awen. So the nine maidens whose breath kindled the Cauldron of the Head of Annwn, as described in the Taliesinic poem Preiddeu Annwn, embody the sense of nine muses, daughters of a god, their breath inspiring awen in the bards they favour.

So their praises also should be sung.

O Muses / O Awenau

You whose breath kindled the cauldron

of awen in Ceridwen’s keeping,

breathe sweet music into my songsfor the gods, for the good life

they shape for us, to celebrate

their presence and their powerto move us and make for us

a world of meaning awakening

the kindled flame of the cauldronburning beneath the brew

of inspired speech in hearts

and minds with devotion that bindsour words in worship, our wish

to bring to all the gods a song

that will please, a gift of praise. -

The Awen in Welsh Tradition

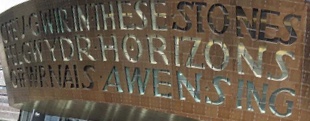

Words from Gwyneth Lewis on the Wales Millenium Centre, Cardiff Although ‘awen’is usually translated literally from Welsh to English as ‘poetic inspiration’ or ‘muse’, its resonance in Welsh is both broader and much deeper. In his poem ‘Mewn Dau Gae’ , the twentieth century Welsh poet Waldo Williams uses the phrase “awen yn codi o’r cudd …” (awen arising from the deep, or from what is hidden). In a commentary on his translation of this poem (1), Rowan Williams says that he didn’t feel able to translate the word ‘awen’ literally here because it would not adequately convey the sense in context, as it is “not just a matter of one poet’s imagination at work”. I would endorse that comment and add that it is just as much a matter of communal inspiration and a shared sense of something arising from the landscape and the ‘Deep’ from which the spirit of the landscape arises.

Rowan Williams further develops his discussion of awen in the Introduction to the translation from The Book of Taliesin which he has published together with Gwyneth Lewis(2). There it is linked both to bardic craft and to “the shamanistic gift of inhabiting a life other than the poet’s own”. Noting that the concept of awen is central to the Taliesin poems, the assertion is again made that simply translating the word as ‘inspiration’ or ‘muse’ would be misguided. Reference to the awenyddion as described by Gerald of Wales in the twelfth century is also made to reinforce the sense of “spirit possession” that the term also implies in these poems, and that this is the mark of a true poet rather than the lesser practitioners Taliesin often denigrates alongside monks and other clerics whose knowledge is seen as inferior to that of the bard.

Taliesin is seen, therefore, as a poet of “ecstatic utterance” and compared to the Greek Orpheus, defining part of the way of ‘being’ a poet. Many of the poems in The Book of Taliesin – both the so-called ‘Legendary’ poems and the ‘Prophetic’ poems – refer to the awen as the source not only of inspiration but of deep knowledge. The source of awen is also often located, both in these poems and in the poetry of other Welsh bards of the period, as coming from the Cauldron of Ceridwen. There is a sense, then, of awen as having a spiritual origin so that, in the more orthodox christian theology of the later Middle Ages, it is seen as coming from the Virgin Mary, or directly from God.

So how has that usage survived into modern Welsh where the dictionaries seem satisfied with ‘poetic inspiration’ or ‘muse’, but the example from Waldo Williams’s poem and Rowan Williams’s commentary on it suggest deeper meanings? ‘Awenydd’, in modern Welsh is often used simply as a synonym for ‘poet’, functioning in a similar way to the word ‘bard’ in English. So ‘inspired poet’ might be a good way of translating it, though it doesn’t usually imply shamanistic possession. Similarly ‘awen’ is what inspires a poet or anyone with a creative gift. It can be used simply in these terms, but the linguistic archive of Welsh still makes that deeper meaning available and the sense of it arising from the ‘Deep’ haunts its usage and implies a deeper mystery to the practice of an awenydd’s craft than simply having a way with words. So Taliesin’s strictures about the necessary qualities of a bard still stand!

1. ‘Translating Waldo Williams’ by Rowan Williams chapter in Cof ac Arwydd , Golygwyd gan Damian Walford Davies & Jason Walford Davies (Barddas, 2006)

2. The Book of Taliesin :Poems of Warfare and Praise in and Enchanted Britain, Translated by Gwyneth Lewis and Rowan Williams (Penguin Classics, 2019) * (Discussed separately HERE~>)

-

Rivers (with nymphs!) flowing across Cors Fochno, map by Wm Hole from Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion (1612) Many rivers and streams run into the drowned lands of Gwyddno Garanhir where Mererid’s~> cry can be heard in the sigh of the turning tides, the cries of the wading birds and the winds gusting over the waves. This is a mythic world in a place that I inhabit. To the north the wide estuary of the River Dyfi washes the salt marsh and the mire of Cors Fochno shadowed by mountains to the east. These lowland acres stretch out to meet the sea, crossed by a web of streams flowing into rivers such as the Clettwr which rushes from the high ground through a rocky cleft and down through a wooded gorge to level out across the bog and into the estuary. And Ceulan, which flows from the same high ground where the cauldron lake of Moel y Llyn, fed by a perpetual spring, drains into the capillaries, veins and arteries around Cae’r Arglwyddes, flooding into the rivers below. Ceulan meets Eleri, running down from even higher ground, and as the land begins to level out they run together through another wooded gorge towards Cors Fochno, once flowing directly into Cardigan Bay but now diverted into the estuary to drain the land between the bog and the sea(*see note). Was it here that Gwion Bach was found in the fish weir of Gwyddno Garanhir and re-born as Taliesin? And so, was the flood that drowned Gwyddno’s realm the same flood that flowed from Ceridwen’s cauldron and poisoned his horses?(Discussion on this and the lake of Moel y Llyn HERE~> )

The geography of the tale of Gwion and Taliesin is diverse. In the most well-known account Ceridwen set Gwion to tend the fire under her cauldron above the waters of Llyn Tegid. But this is too far north of Maes Gwyddno for the watersheds to bring the flood from there, though Llyn Tegid is itself said to have been formed by an inundation. Other parts of the tale of Gwion and Taliesin take it even further north to the Conwy estuary on the northern coast of Wales, where yet another inundation legend is set. Gwyddno himself may have originated in the ‘Old North’, that is the borderlands between England and Scotland.

So these ‘legendary’ events have geographical fluidity! But what of their source myth? Here, at the crucial meeting place of legend and mythic narrative – and the liminal ground of folklore through which the stories are diffused – is where historical memory, geology, and cultural ancestry come together in inherited mythos, and so cultural identity. It tells us where we belong, and who our gods are. When Gwyddno Garanhir leaves his lands to dwell with the ancestors accompanied by Gwyn ap Nudd ~> it is a mythic event represented in legend as located in a specific place, though his land could be any of many where historical inundations took place or where geological events re-shaped landscapes and seascapes as the narratives of these events themselves become ‘folklore’ and are written down as ‘literature’. They are our events when they are located in familiar landscapes or narrated in culturally specific ways. But the mythos is universal and this universality is reflected in the apparent universality of international folklore motifs, though mythic universality runs deeper; this is why Annwn is the ‘Deep’ from which our shallow world is manifest.

But it is never ‘shallow’ to us. because it is given depth by legends and mythic narratives which enliven the lands we inhabit, just as the empty winter woods take on a depth when sunlight shimmers through trees in full leaf to shadowy hollows and glades. Already, then, when Taliesin is re-born in Gwyddno’s lands, they are places of legendary history where mythic events have occurred. So when Gwyddno’ son Elffin adopts Taliesin as his bard at the court of Maelgwn Gwynedd, characters from the historical record become the stuff of legend and the carriers of mythic narrative: here the bard re-born from the waters to sing of the Deep from which he came. Here too is Mabon, freed from the dungeon below the waters of the Severn, who himself shares a story with Pryderi, stolen from his mother, Rhiannon, soon after his birth. The stories are told with many variations and inter-leavings as myth becomes legend and lore: the Harp of Maponos ~> playing to inspire multiple narratives.

And Taliesin? His historical, legendary and folkloric dispersal weaves a mythic identity as the archetypal bard. But when Gwyn ap Nudd invites him into The Deep~> he seems reluctant to leave the legendary territory of his shaping for the mythic realm he claimed to know. Such is the ambiguous fate of heroes and demi-gods of ancient story, living between worlds. It is so for us too, when The Deep reveals itself and its darkness illuminates our world.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.