Troi at hen iaith, at gyfoeth hanes, at faeth

meysydd yr oesoedd coll; darganfod

pob haenen llên yn hanu o bob cenhedlaeth

a dilynant hyd heddiw: brithiaid yn eu hanfod.

In the early 1990’s I published a series of interviews with translators in the magazine Materion Dwyieithog / Bilingual Matters which was produced as projects with students on a course I taught at the time.

These included lengthy interviews about translation and original work from Tony Conran and Joseph Clancy which seem worth putting on a more permanent record. So I have made pdf versions of the relevant pages from the editions available for free download HERE~>

My local Welsh-language community magazine has a regular column on the origins of place names. A recent edition discussed a farmhouse located on a rocky outcrop at the edge of Borth Bog (Cors Fochno) called ‘Cerrigcaranau’ (1) which seems to mean ‘Crane Rock’. Cranes were once common in Wales and this wetland would be an appropriate place for them, although ‘garan’ was also sometimes used instead of the more usual ‘crychydd’ or ‘Crëyr’ for ‘heron’, but perhaps only after cranes were no longer present.

Another possible source of the name was also discussed by a local writer in 1910: that the reference is to Gwyddno Garanhir and that the rock’s name might have originally been ‘Cerrig Garanhir’ referring to the drowning of his lands as recounted in the legend of Cantre’r Gwaelod, indicating that Gwyddno took refuge from the flood on this piece of higher ground (2). The suggestion here is that it refers to Gwyddno’s name ‘Garanhir’ (literally ‘long crane’, though it has been interpreted as meaning he had long legs like a crane). But if Gwyddno, as a legendary character, has a crane nature, might this also have mythological origins? Cranes feature in a number of ways in mythology. The Gaulish god Tarvos is represented in images of him as a bull with three cranes. Miranda Green, in a discussion of the image, has suggested that cranes and other water birds can represent the release of the soul after death and more generally function as an image of metamorphosis or transformation into animal form. (3)

Although it is difficult to locate the origins of the Cantre’r Gwaelod legend precisely in time, in the version that we have it seems to post-date the references to Gwyddno as ruler of this land at the time of the localised Taliesin story, that is if we take it literally as the Taliesin story must be set before the inundation. The two stories may have different provenance and become entwined in local legend, just as they each have parallel versions set on the Conwy estuary in North Wales. But Gwyddno’s crane nature, if it has mythological origins, would go back even further, before the legendary events that these stories relate. To shape-shift and fly from an inundation, or to transform into a creature capable of remaining on flooded land and become one with the transformed environment, takes the story back before the legendary domain of historical or geographical events, imaginatively shaped into story, to the mythological domain which often infuses such legendary narratives with deeper significance.

What, then, of Gwyddno’s ‘conversation’ with Gwyn ap Nudd? There is no mention there of Gwyddno’s drowned lands, but he remains a legendary character encountering a mythological one who may be gathering his soul after death. This does not preclude the legendary Gwyddno himself having a mythological origin, or that his soul bird might have been a crane, released by Gwyn as the ‘Bull of Battle’ just as Tarvos may be releasing transformed souls as cranes. Such speculations are enticing and chime with my own perceptions of cranes, herons, egrets as wide-winged soul-birds traversing the spirit world whenever I encounter them in feathered flesh or in ethereal space.

—-

1 Angharad Fychan ‘Enwau Lleoedd’ Y Tincer, Mawrth 2005.

2 Richard Morgan ‘Dwy Neidr’ Cymru 38 , t.55

3 Miranda Green Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend, p.68 & p.208

A major influence on John Rhŷs, the author of Celtic Folklore (1901), according to Rhŷs himself, was the the Welsh-language writer and folklorist Glasynys (Owen Wyn Jones) who, in the middle of the nineteenth century , wrote a series of accounts of the way festivals such as Calan Gaeaf were celebrated in rural areas in the mountains of North Wales, as well as tales about the Tylwyth Teg which were then still actively resonant in the imaginative life of these communities. His accounts were, in the words of one later commentator, shaped “in his own mould”[vii], seeking to recreate their essential core of the origins of the traditions he related. Here is the opening of his account of a Nos Galan Gaeaf Celebration:

“Whoever wishes to see and hear the traditional customs practised through the ages should come with me to Cwm Blaen y Glyn where they have been observed since time immemorial. There, in the quiet of the mountains, the young, adults and old folk gather together to celebrate Nos Galangaeaf.”

He describes how the evening begins with a large bonfire being lit on the hill above the valley. When the fire lighters have returned, the evening’s proceeding begin featuring the final fruits of the year’s harvest: apples and nuts. The apples are put in a tub of water and have to be removed by the younger attenders using only their teeth to pick them up, a custom known more generally as ‘apple bobbing’. A more adventurous version of this game for young adults was to stick a lit rush candle into the apple and players had to attempt to eat it without holding it in their hands, and without burning their cheeks! While this is going on oatcakes are cooked on a griddle on the fire and homemade mead is dispensed to the company.

The festival is also a time for divination. This is where the nuts come in. Those wishing to know if they will have good luck for the coming year put one of the nuts into the fire. Each one that cracks with a ‘clec’ means good luck. But if the nut burns without cracking it means bad luck.

At this point an awaited guest arrives: Rhydderch y Grythor who will provide music with his crwth or traditional fiddle. Traditional songs are sung, one such with a verse that may be translated something like this:

In the house there’s nuts to crack

For tonight is Calan Gaeaf;

In by the fire mead to drink,

Outside the Hwch Ddu Gwta.

The ‘Hwch Ddu Gwta’ or ‘Tailess Black Sow’ will chase anyone out after dark on this night, and woe betide anyone who is caught. Those within by the fire are safe for now. But for those whose nuts did not ‘clec’ in the fire, what may be their fate on their way home under the stars at the dark of the Moon beneath the far glitter of Orion’s belt where the Grey King haunts the skies?

As well as writing descriptive accounts such as this, he also incorporated traditional lore into short stories such as Y Fôr Forwyn (The Mermaid) where the traditional tale of a fisherman who meets and marries a mermaid is shaped into a more complex narrative where the Mermaid (Nefyn) is said to be the daughter of Nefydd Naf Neifion and the niece of both Gwydion ab Don and Gwyn ap Nudd, and in which the children of the marriage have to deal with its various consequences in both the human and the otherworld. Rhŷs recounts part of this tale in Celtic Folklore alongside others concerning the descendants of such mixed marriages including one where he states that “Glasynys maintains that [the descendants] were known to him at the time he wrote in 1863”.

Another appreciative account of his contribution to Welsh life records that he “…gave tongues to our old castles and our ruined forts, told the legends of our brave forbears and threw a magical aura over daily life through an expressive use of the Welsh language that was music to the souls of its speakers.” [xxiii]. Glasynys himself held this as a mission in a world where such things, he felt, were slowly being eroded from consciousness, saying in a essay of 1860 :

“The world has turned. Children are no longer raised to value such things. No care is taken to nurture an awareness of them so the result is that the world has shrunk, is weakened, is shrivelled and withered. The soul is not contained within the land and the life of the land, nor transformed in a view of the world which is its pattern or archetype.” [xxv]

This sense of the value of folklore as an expression of the spiritual health of society is an early identification of what, in our own time, has been described as ‘the disenchantment of the world’. But Glasynys, though he saw things were changing, still looked at rural life in Wales as an Arcadia, not only in the past, but still existing for him in the present.

Translated / paraphrased from the selection Straeon Glasynys ed. Saunders Lewis (1943) All quotations followed by roman numerals are references to the Introduction to this edition.

A major influence on John Rhŷs, the author of Celtic Folklore (1901), according to Rhŷs himself, was the the Welsh-language writer and folklorist Glasynys (Owen Wyn Jones) who, in the middle of the nineteenth century , wrote a series of accounts of the way festivals such as Calan Gaeaf were celebrated in rural areas in the mountains of North Wales, as well as tales about the Tylwyth Teg which were then still actively resonant in the imaginative life of these communities. His accounts were, in the words of one later commentator, shaped “in his own mould”[vii], seeking to recreate their essential core of the origins of the traditions he related. Here is the opening of his account of a Nos Galan Gaeaf Celebration:

“Whoever wishes to see and hear the traditional customs practised through the ages should come with me to Cwm Blaen y Glyn where they have been observed since time immemorial. There, in the quiet of the mountains, the young, adults and old folk gather together to celebrate Nos Galangaeaf.”

He describes how the evening begins with a large bonfire being lit on the hill above the valley. When the fire lighters have returned, the evening’s proceeding begin featuring the final fruits of the year’s harvest: apples and nuts. The apples are put in a tub of water and have to be removed by the younger attenders using only their teeth to pick them up, a custom known more generally as ‘apple bobbing’. A more adventurous version of this game for young adults was to stick a lit rush candle into the apple and players had to attempt to eat it without holding it in their hands, and without burning their cheeks! While this is going on oatcakes are cooked on a griddle on the fire and homemade mead is dispensed to the company.

The festival is also a time for divination. This is where the nuts come in. Those wishing to know if they will have good luck for the coming year put one of the nuts into the fire. Each one that cracks with a ‘clec’ means good luck. But if the nut burns without cracking it means bad luck.

At this point an awaited guest arrives: Rhydderch y Grythor who will provide music with his crwth or traditional fiddle. Traditional songs are sung, one such with a verse that may be translated something like this:

In the house there’s nuts to crack

For tonight is Calan Gaeaf;

In by the fire mead to drink,

Outside the Hwch Ddu Gwta.

The ‘Hwch Ddu Gwta’ or ‘Tailess Black Sow’ will chase anyone out after dark on this night, and woe betide anyone who is caught. Those within by the fire are safe for now. But for those whose nuts did not ‘clec’ in the fire, what may be their fate on their way home under the stars at the dark of the Moon beneath the far glitter of Orion’s belt where the Grey King haunts the skies?

As well as writing descriptive accounts such as this, he also incorporated traditional lore into short stories such as Y Fôr Forwyn (The Mermaid) where the traditional tale of a fisherman who meets and marries a mermaid is shaped into a more complex narrative where the Mermaid (Nefyn) is said to be the daughter of Nefydd Naf Neifion and the niece of both Gwydion ab Don and Gwyn ap Nudd, and in which the children of the marriage have to deal with its various consequences in both the human and the otherworld. Rhŷs recounts part of this tale in Celtic Folklore alongside others concerning the descendants of such mixed marriages including one where he states that “Glasynys maintains that [the descendants] were known to him at the time he wrote in 1863”.

Another appreciative account of his contribution to Welsh life records that he “…gave tongues to our old castles and our ruined forts, told the legends of our brave forbears and threw a magical aura over daily life through an expressive use of the Welsh language that was music to the souls of its speakers.” [xxiii]. Glasynys himself held this as a mission in a world where such things, he felt, were slowly being eroded from consciousness, saying in a essay of 1860 :

“The world has turned. Children are no longer raised to value such things. No care is taken to nurture an awareness of them so the result is that the world has shrunk, is weakened, is shrivelled and withered. The soul is not contained within the land and the life of the land, nor transformed in a view of the world which is its pattern or archetype.” [xxv]

This sense of the value of folklore as an expression of the spiritual health of society is an early identification of what, in our own time, has been described as ‘the disenchantment of the world’. But Glasynys, though he saw things were changing, still looked at rural life in Wales as an Arcadia, not only in the past, but still existing for him in the present.

Translated / paraphrased from the selection Straeon Glasynys ed. Saunders Lewis (1943) All quotations followed by roman numerals are references to the Introduction to this edition.

Looking to put together a compilation of writings from here and elsewhere, it seemed that something on Nodens was also needed. So here is a draft of some thoughts which might make it into such a compilation. It relies less on historical attestations and academic investigation than other pieces. But there are a number of ways that data from historical sources, folklore and archaeology link into my personal insights.

There is a temple of Nodens above the River Severn at Lydney, facing across the river from the western side and the eastern edge of the Forest of Dean. The temple was constructed quite late in the Roman occupation of Britain and so would have been thoroughly Romanised in its practice though dedicated to a Brythonic god Nodens who has survived in the folklore record variously as Nudd, Lludd and Lud. There are a number of landscape features in the forest containing the element ‘Lyd-’ which I once spent some time pursuing on foot [Described HERE]. This area between the rivers Severn and Wye, and westwards into the old forest of Wentwood, was known as ‘Gwent Is-Coed’ (‘Gwent below the Forest’) and, according to the first Mabinogi story featuring Rhiannon and Pryderi, Gwent Is-Coed was the domain of Teyrnon who rescues Pryderi after he had been snatched as a baby from Rhiannon by a creature who is also intent on stealing a foal from his stable every May Eve. Teyrnon eventually returns Pryderi to Rhiannon, ending her penance at the horse block for allegedly murdering her son. He is one of four fathers for Pryderi alongside his other foster-father Pendaran Dyfed, his biological father Pwyll Pen Annwn and, when he is an adult, his virtual step-father Manawydan. Pryderi is, of course, an analogue of Mabon Son of Modron, the Divine Son Maponos of the Divine Mother Matrona, so it is appropriate for a character who is based on a god whose identified descent is matrilineal that his fatherhood should be more diversely identified. Whether we are to regard each of these fathers as aspects of one divine figure, or different expressions of male partners for the Divine Mother, it is instructive to note that the name Teyrnon as been derived from Brythonic Tigernonos (‘Divine King’), an appropriate partner for Rhiannon whose Brythonic origin in Rigantona (‘Divine Queen’) suggests that they should be placed together. Consider, too, that an early version of a triad(*) which predates the Mabinogi story claims that Pendaran Dyfed was the original owner of the Otherworld pigs that Pryderi loses to Gwydion in the fourth Mabinogi and so might be conflated with Pwyll Pen Annwn who was in later versions said to be the recipient of the pigs from Annwn. Finally consider that Manawydan has been associated with the Irish sea god Manannan, in spite of himself having no apparent maritime characteristics in the Welsh sources, but may also be conflated with Pendaran as he also becomes a lord of Dyfed when he marries Rhiannon.

It is my intuition that we can we regard each of these characters as expressions of Nodens and that he is a sea god whose temple at Lydney overlooks the lower reaches of the River Severn where it broadens to the sea and where the phenomenon known as as the ‘Severn Bore’ causes the river to reverse its downwards flow and rush back upon itself with the incoming tide. This, it has been suggested, is an explanation for the epithet ‘Twrf Lliant’ which may mean ‘thundering waters’ and is attached to Teyrnon’s name. That is, the wooded domain of Teyrnon by the tidal Severn, where the temple of Nodens is located, the land of Dyfed much further west — the domain variously of both Pendaran and Pwyll and later of Manawydan — might all be earthly locations for characters who carry the mythology of Nodens, though not explicitly of the sea. If all of these have their origins in earlier folklore based on even earlier mythology, there is also a much later folktale in Welsh which tells of a character called ‘Nodon’ who was lord of the vast plain which now lies under the sea between Wales and Ireland. The tale tells that a healing well was kept for him by a well maiden called Merid, whose violation caused the land to be flooded. This is clearly a variant on the story of Mererid and the drowning of Cantre’r Gwaelod recorded in The Black Book of Carmarthen. But this story refers to a much larger area than the lands of Gwyddno Garanhir and is ruled by a character who is clearly Nodens.

Consider that flooded plain in the context of the words in the second Mabinogi where Bran crosses to Ireland: “… the sea was not wide then and Bran waded across the two rivers Lli and Archan. It was later that the sea flooded across the realms between.” Legends reflecting the historical raising of the sea levels in earlier times also carry mythological significance. Bran is Manawydan’s brother and is portrayed as a giant because of his characteristics in the Mabinogi, though he is never specifically referred to as a giant. The two brothers are clearly beings from the mythos as well as characters in the story, and if we can associate them with the sea, as we can their Irish counterparts, and the sea as a primordial place of origins, and Nodens as the Sea God, then those who are related to him as brother, sister, child or alter-ego — god relationships are fluid — can also be seen as having their identity not as ‘equivalents’ or syncretised deities but as springing from a source in the primordial deep, manifesting now perhaps as Annwn, or the deep place of origins, in the keeping of Gwyn ‘son’ of Nudd or Nodens; or the legendary dimensions of Gwent Is-Coed or Dyfed. When there is an enchantment on Dyfed in the third Mabinogi, and both Rhiannon and Pryderi are taken back to the Otherworld, that land becomes wild and uncultivated as it would have been before people lived in it. When Manawydan brings them back the land returns to its cultivated state and the people who live on the land have also returned. Just as the gods move between the worlds, and bring their world into our world, so they also make our world what it is, a place we can inhabit when the gods as cultural beings are with us, but we are also reminded of their primordial origins and that other place which the sea washing over the land also represents. What is given may also be taken away. A salutary reminder for our times.

* “And Pryderi son of Pwyll Pen Annwfn, who tended the pigs of Pendaran Dyfed in Glyn Cuch in Emlyn.” (TYP 26)

The sculptures of the Welsh artist John Meirion Morris (1936-2020) encompass a range of ‘spiritual’, ‘political’ and ‘cultural’ subjects, including a number of portaits of Welsh poets, portrayed in a way that brings the living presence of the awen into the hard materials of the sculptors craft.

His spiritual subjects often include references to mythological characters and objects such as the ‘Pair Dadeni’ (Cauldron of Rebirth) illustrated above, Gwydion’s Hudlath (magic wand), and studies of Rhiannon, Bran, and others characters from the Mabinogi.

Always engaged with the essence of his subjects rather than sentimental idealistion his shapes and materials achieve an uncompromising solidity rather than the ethereality that often characterises such subjects but their life shines through the apparently intractable matter of their construction.

A glimpse of this in the brief video and on his website referenced below.

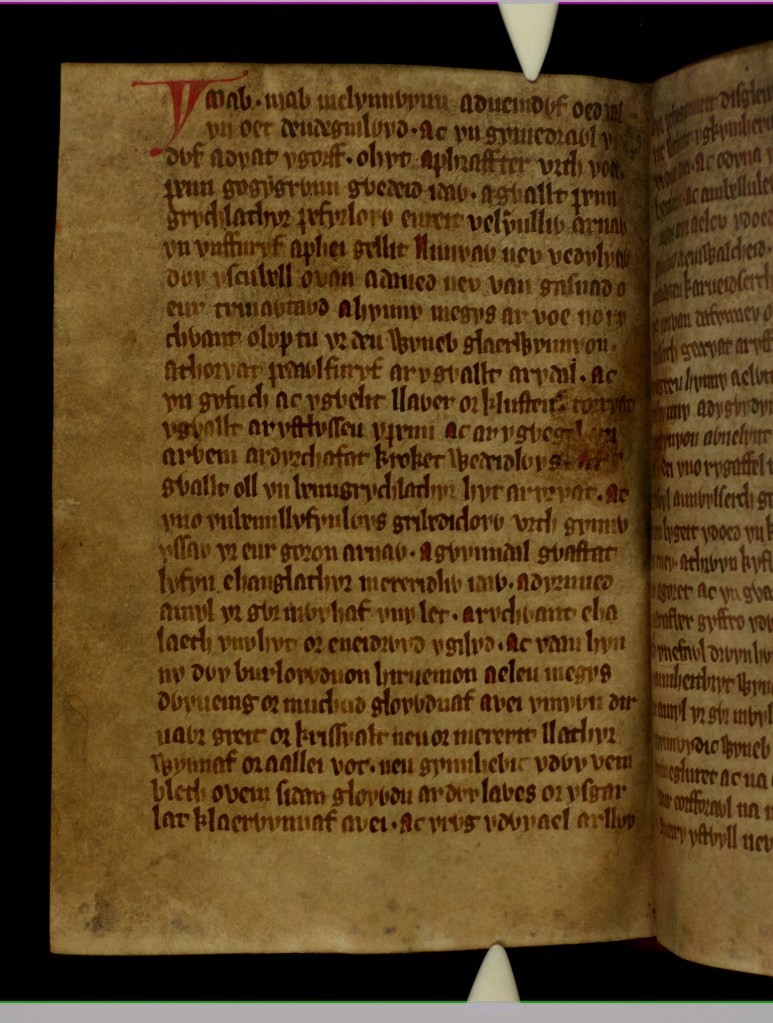

A page from a medieval mss copy of Ymborth yr Enaid

Ymborth yr Enaid (Sustenance of the Soul) is a text written in the 13th century by a member of the Dominican order of friars in Wales. It sets out a guide to mystical experience and suggests a number of practices to enable such experience for members of the order. As such it is comparably rare in the literature of medieval Europe in that the orthodox view of the Church at the time discouraged attempts to experience divinity directly rather than through the established rituals of the Church, and held that such experience, if it did come, should come unbidden and then only to special individuals whose experiences, if recognised by the Church, might well lead either to sainthood, or, particularly in the later Middle Ages, to accusations of heresy for the individuals concerned.

The fact that Ymborth yr Enaid was written in Welsh rather than Latin suggests that it was intended as a guide for ordinary members of the Dominican order rather than as a contribution to theological debate, and also meant that it would have escaped the attention of a wider audience outside Wales. One scholarly monograph on the text* suggests that a context for the production of the work in Wales might be the native tradition of the awenyddion as described by Giraldus Cambrensis in the 12th century. Although this tradition is more likely to have arisen from remnant druidry, and is described in terms of inspired prophetic ability, it is suggested that the existence of such a tradition would have provided the author of Ymborth yr Enaid with a context for a guide to mystical experience, or, as the opening section puts it, to “the ecstasies” and ”visions” whch may come “from the Holy Spirit” and “the nine orders of angels”. The fact that some parts of the work are in verse, and others in what might be termed ‘heightened prose’ indicate that the author was also relating personal inspirations alongside the more mundane passages of discursive argument.

The starting point for those seeking mystical experience is the conventional advice which would be given to all members of medieval monastic orders: avoid sinful thoughts and practise virtuous acts. This would attract the love of God which should be reflected to others around the practitioner. Having achieved this ideal state, the specific practices to achieve mystical experience can then begin. The author’s own experiences, as related here, concern a vision of the young Jesus and advice given by him to the poets that he should be the object of their praise. Clearly, the author was considered to be one of these poets and the instructions for achieving mystical visions follow the advice often given to poets who might compose intially by lying down in a darkened room shaping the verse in their minds. So the seeker of mystical experience is likewise directed to do so at quiet times of day or at night in bed “after midnight until daytime”. The aim here is to induce trance-like states, variously defined as “twofold”, “threefold” and “victorious” trance, each stage taking the practioner further from the physical flesh until a total union with the divine is acheived. Also significant is that the trances are to be experienced by individuals quietly in private spaces rather than as part of community worship or ritual, although part of the preparatory instructions include chanting a Latin hymn which the author has translated into Welsh metrical form. This should be done until “the heart dances and sings with devoted love”. While they are clearly distinct, and operate within different contexts, the similarities between the instructions to poets and to the Dominican friars, and between the trance states of the awenyddion and those which might be achieved by the friars, suggest a persistence within Welsh culture in the early medieval period of the notion of spiritual, poetic and prophetic activity arising from mystical experience, and spilling over from the bardic tradition of the divine origin of the awen to the Christianity which had become the approved mode of spiritual experience .

If the medieval Church, in general, tended to be suspicious of the bards and of poetry as a medium for individual expression, what we find here is a work in which poetry is integrated into both descriptive and imaginative prose detailing practices which may be undertaken by individual members of a religious order which was part of the medieval christian establishment. It is likely, that the anonymous author was also a bard as the verses included in the text display knowledge of techniques that are likely to be the result of bardic training. Analysis of the style also shows it to be comparable to works of imaginative prose tales of the period, even leading to suggestions of possible common authorship.* Be that as it may, the author was certainly gifted with the awen and able to accomodate older ascriptions of its divine origin to contemporary religious orthodoxy. The stories that shape divine inspiration change over time. The mythologies that give it form and make it accessible to expression vary across cultures with different emphases, aspirations and political priorities that may seek to channel it to orthodox interpretations or even suppress it entirely. But whatever the language of religious expression, it seems that divine inspiration is a universal quality which can shape itself to any available medium that doesn’t seek to stifle innovative expression of visionary experience. The question remains, of course, as to whether it comes from a single source which is experienced differently in different cultures, or whether the sources are various but lead to a similar mode of human experience. Suffice to say that the experience itself is definitive for those who have it.

* R. Iestyn Daniel A Medieval Welsh Mystical Treatise, (University of Wales Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, 1997). The author suggests that the idea of divine poetic inspiration originated in “ a Christianization of a pagan belief that the poet, when inspired, was possessed by an impersonal underworld power”.

A discussion of the manifestation of this idea in the early welsh bards can be found in : Y Chwaer Bosco ‘Awen Y Cynfeirdd a’r Gogynfeirdd’ Beirdd a Thywysogion (Caerdydd, 1996).

R Iestyn Daniel has also edited an edition of the medieval text:Ymborth yr Enaid, (Caerdydd, 1995).

For a discussion of the place of Ymborth yr Enaid in early Welsh religious thought and a partial translation of the text into English see: Oliver Davies Celtic Christianity in Early Medieval Wales (Cardiff, 1996).